Sabbatical

Originally Posted July 27th

Since completing my PhD in 1999 I have been teaching full-time for 7 straight years. In that time I have taught over 2 000 students at four different universities in England, Scotland and Canada. This coming year I am on sabbatical, my first sabbatical ever. By comparison to most academics, this first sabbatical is long overdue.

By moving from various universities, first within the UK, and then back to Canada, I in effect forfeited a sabbatical. Each of these moves were moves I was of course very happy to make. So the fact that I started afresh each time, in terms of sabbatical credit, did not bother me.

Furthermore, I love teaching and sincerely believe that teaching and research go hand-in-hand. So teaching at different institutions, and in different disciplines and countries, has really benefited my intellectual development and thus I don’t feel the absence of a sabbatical has in any way hurt my research. But the chance to spend this coming academic year with a more focused attention on my research programme is something I look forward to with much anticipation and enthusiasm.

Those outside of academia might wonder what, exactly, is a sabbatical? Here at Waterloo University the stated policy on sabbaticals is as follows:

“The purpose of a sabbatical leave is to contribute to professional development, enabling members to keep abreast of emerging developments in their particular fields and enhancing their effectiveness as teachers, researchers and scholars. Such leaves also help to prevent the development of closed or parochial environments by making it possible for faculty members to travel to differing locales where special research equipment may be available or specific discipline advances have been accomplished. Sabbaticals provide an opportunity for intellectual growth and enrichment as well as for scholarly renewal and reassessment”.

I genuinely share the sentiments expressed in this policy, and so I take my sabbatical responsibilities very seriously. The fact that Canadian tax-payers pay my salary means that I must justify, to them, why they are paying for my sabbatical. Academics should not view sabbaticals as something they are simply entitled to; rather it is something that must be earned and it carries weighty responsibilities.

The fact that I see a sabbatical as something one must justify has motivated me to write this post, to offer some reflections on why a sabbatical is important (not just to the academic him or herself, but to society-in-general) and what I intend to do during my upcoming sabbatical.

To justify taking a sabbatical one must first place the purpose of a sabbatical in the larger context of the value of institutions of higher education more generally. Universities promote many important societal interests. They help train students to perform the specialised jobs which the global market demands of Canadian workers if we are to remain competitive and at the cutting edge of the global market.

But universities do much more than this. Universities also disseminate knowledge about important intellectual traditions (e.g. an appreciation of human history and art, etc.) and help cultivate valuable intellectual skills (e.g. critical analysis, communicative skills, etc.). These traditions and skills are both intrinsically and instrumentally valuable. They enhance a student’s quality of life by exposing him/her to new ideas and help equip them with the skills necessary to exercise their practical reason and pursue intellectual freedom. And higher education also benefits society in general. An educated citizenry is vital to having a healthy, tolerant polity.

So universities serve a diverse array of important economic, social and moral purposes. An academic’s sabbatical plans should be shaped by an appreciation of the values that inform higher education more generally. And the UW stated sabbatical policy captures those nicely.

Of course academics will have to balance their career responsibilities with other commitments, such as their familial responsibilities. These responsibilities might make it difficult, for example, to physically relocate the family during a sabbatical term. One’s spouse might have career obligations that limit a family’s mobility, or one might have children and/or financial constraints that limit what one can do. So like most things in life, figuring out what the right thing to do during one’s sabbatical is difficult and requires much reflection, deliberation and compromise.

Bearing these diverse considerations in mind, I put a lot of time and energy into planning my sabbatical this year, hoping that all these pieces of the puzzle would (eventually!) fall into place. Ideally, I would get the chance to go somewhere that would truly enhance my intellectual growth and also be something that would be viable in terms of relocating the family (who would have to come with me). But even the best intentions and planning also needs some luck…

I have been very fortunate to have the opportunity to do something that gives me all of things I hoped for and more. I have been awarded a research fellowship to spend a year at the Centre for the Study of Social Justice at Oxford University. While there I will work on my book on genetic justice, and contribute to the activities of the Centre (e.g. contribute to seminars, conferences, etc.). This new book aims to generate a greater awareness of, and help us address, the pressing social, ethical and legal challenges which the genetic revolution has thrust upon us. I have already published a series of articles on these issues (see here, here, here and here).

Why do I think this research is important? A sample of some of my blog posts (here, here, here and here), as well as those of others, should, I hope, convince you that these are important issues worth taking seriously. The values and interests at stake in addressing the genetic revolution are those integral to social justice. And this is an area of study that must be *interdisciplinary*. Having the opportunity to spend the year working at the Centre for the Study of Social Justice is perfect. The Centre’s stated purpose and mission is as follows:

“The Centre for the Study of Social Justice is a forum for Oxford's distinguished grouping of political theorists to share their expertise, collaborate on research projects and publicise their work to the broader academic and policy-making community. Questions of social justice cover a wide range: philosophical and practical, theoretical and applied, global and domestic. Encompassing this variety the Centre provides a unique opportunity for cutting-edge intellectual exchange on a subject of fundamental political significance. The Centre aims to make connections and build bridges: between different aspects of the theoretical study of social justice; with other disciplines such as Philosophy, Law, Economics, Sociology and Social Policy; and with the "real world" of politicians and think-tanks”.

So from a career perspective, being awarded this fellowship is absolutely perfect. I couldn’t have hoped for more. There are a number of excellent people at the Centre, and at Oxford more generally, and interacting with these scholars will be very beneficial to my intellectual development.

As for relocating my family, the fact that my wife and I have already lived in the UK for 7 years, and both are children were born there, should make things much more easier than it would be for someone in a different situation. We have a great deal of friends from various places in the UK that we look forward to seeing during our stay. And our children, who left the UK when they were very young (though they are still young), are looking forward to returning to the cities they were born in and have heard many stories about.

And finally, Oxford is a very beautiful city (see this and this).

So this coming year, my first sabbatical, is extra special for a number of reasons. It’s a great adventure that we are all looking forward to. Of course preparing to relocate the family overseas is also very stressful and time-consuming. And I only have a few weeks left to sort out a million things. Thus I’m afraid the blogging will be light until we are settled on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean.

I might “recycle” a few posts, reviving some substantial posts from the archives. And I expect to return to a more regular posting schedule in the Fall term, no doubt with some posts on our experiences of living in Oxford for the year. It should be a fun year!

I hope you visit the blog to hear how things are going.

Cheers,

Colin

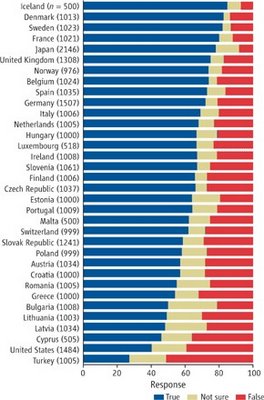

Why does the US rank so low on the acceptance of evolution? The authors provide the following explanation:

Why does the US rank so low on the acceptance of evolution? The authors provide the following explanation: